Or: Sam's Year 2014 In Proverbs

Antonio Machado

Caminante, son tus huellas

el camino y nada más;

Caminante, no hay camino,

se hace camino al andar.

Al andar se hace el camino,

y al volver la vista atrás

se ve la senda que nunca

se ha de volver a pisar.

Caminante no hay camino

sino estelas en la mar.

Wayfarer, the path is made

by your passage, nothing more;

wayfarer, there is no roadway,

for it is made by your journeying.

By walking you make the way,

And turning, you look back to see

the path which you will never

tread again.

Wayfarer, there is no roadway,

Only wake trails on the wild sea.

2014 In Review

That “something” was adventure. Change. Differentness. Disruption of routine. So within days of starting 2014 I grabbed life by the horns, jumped on and hung on for dear life during the wildest ride of my life.

During January through March of 2014 I prepared for my journey. I left my job as a nurse practitioner in Arizona and headed west to Japan in April, embarked on many adventures and foolishness, and ended up back in Tucson from the east just as November began. I spent the final two months of the year recovering from and reflecting on that journey, as well as preparing for my next one.

I present to you 29 life lessons I learned in my first trip around the world.

January - It Begins

Lesson 1: “The Simple Things Are Also The Most Extraordinary Things"

Yes, I wanted to have grand adventures, and I did. But what I wanted most out of my sojourn was to experience simple daily gestures and happenings in a new place and a new way.

I felt stultified by years of intense unvarying routine. I was working 60 hours every week with almost zero downtime. The few times I did escape on vacation, I would come back to a huge mess that took weeks to fix. Balls were dropped. Patients suffered. I mourned the loss of my free time.

I wanted to experience the simple things in life as new again. I wanted to have to think about what to have for breakfast, instead of always eating the same thing. I wanted to walk in new places, with new people, and think new thoughts.

Be careful what you wish for.

Lesson 2: “Patients” Is A Virtue

I felt reprehensible for not telling them, so I doted on my patients even more than usual. I stayed late. I even came in early. The former is easy for me, but the latter is practically unthinkable. But I did it anyway, to assuage my self-directed guilt and dot every “i” and cross every “t” for the provider coming to take over the clinic.

Somehow, I managed to remain patient through the whole month, until the very end. I found out who was taking over the clinic, and it was fantastic news. I knew that my patients would be well taken care of in my absence.

Relieved of my guilt, I instantly stopped working so many extra hours and went back to my usual hardworking self, rather than my “oh-dear-God-what-were-you-thinking” self-immolation overworking self.

February - Prepare ye

Lesson 3: It Ain’t Easy To Say Goodbye

And it sucked.

Almost without exception, saying goodbye was pure unadulterated misery. Every day at least one patient cried, and the record was four in one day. I had to wait to go home so that I could cry, because I needed to be there for them, and hold the space for them to be vulnerable. I reassured them that they would be well taken care of by my successor, a model nurse practitioner and human being.

“But it’s not the same,” they would say.

“I know,” I would respond. “I’m sorry. But I have to go. This is part of who I am.”

I could explain all I wanted, but the pending separation wounded them and me deeply. I was walking on hot-coal-eggshells all day long, and on returning home at the end of the day, I would slump into my chair, exhausted, drained, sucked dry.

Lesson 4: It Is Better To Light A Candle Than Curse The Darkness

The most common reaction to my studying Japanese was “but it’s so hard!!! How can you ever possibly learn Japanese?!?” The subtext of the conversation was invariably “that’s impossible; you should give up now.” Well, I’m a firm believer that those who say a thing is impossible shouldn’t get in the way of those who are doing it.

Sure, I want to speak and read Japanese like a native, and be all smooth and perfect and all that jazz. But my true motive is the learning itself. I love coming to understand how a completely different culture thinks, feels and acts. I love understanding their sayings, their movies, and how they conduct their relationships.

My favorite part of language learning is the “aha!” moment when you connect something from a language to a cultural norm, more or folkway of its speakers. No, I won’t curse the darkness of not knowing. I’ll just light my tiny candles, one by one, until I can see another world via this new way of communicating, and new way of knowing. That is why I study languages.

March - Feel The Burn(out)

Lesson 5: Where There’s A Will There’s A Way

Therefore, I had the bright idea to write a book.

Yes, I’m serious. In my defense, it was a book about surviving burnout. I needed a repository to help myself deal with the burnout, as my time-tested methods were beginning to simply fail outright. I knew I needed an anti-burnout strategy, and that if I just sailed off into the wild blue yonder, I would not accomplish my goal of becoming un-burned-out. This burnout was too deep to approach without a solid plan.

I had searched and searched for a resource specific to nurse practitioners to help guide me through this process, but didn’t find one, so I settled on creating it myself, and got to work. In the middle of my final 6 weeks before launch to parts unknown.

Despite the utter lunacy of the idea, it all came together. I have no idea how, but I needed it to happen, so I made it happen, and benefitted from it tremendously as I began my burnout-busting odyssey.

Lesson 6: All Good Things Must Come To An End

I gave up everything that did not go toward a) publishing my book or b) preparing for my launch to Japan. I worked harder for these two things in these six weeks than I ever have in my life. The most difficult part was not having the depth of energy and mental health resources to help those around me when they were hurting.

However, everything that did not get me closer to a) or b) went on autopilot, and by some miracle everything came together as planned, so that I could publish my book and launch myself to Japan on time and prepared. I’m proud of what I accomplished, but I’m just as glad it is over.

April - Launch To Japan

Lesson 7: Some Days Are Better Than Others

I bumped myself up to the Intermediate (level 3 of 5) level with permission of the principal, but it was much too hard for me. I struggled mightily in this class, barely following the explanations of grammar points, let alone understanding them. It took until several months in before I even learned correct grammar terminology.

The day I learned the word “keoshi” (adjective) was not one of my shining moments. I think I will always remember the way the teacher’s face fell when she finally realized that not only did I not understand the grammar point, but it was because I didn’t know what the word “adjective” meant.

I was happier in the harder class, though, and made several friends, so even though I struggled so hard, I never seriously thought about going back down to the easier level. I came to Japan to learn, and I learn more when challenged, so even though I had some hard days, overall it was worth it.

Lesson 8: Privilege Is Driving A Smooth Road And Not Even Knowing It – Brene Brown

85% of the students in my school (and other language schools in Japan) are students from poor Asian countries who come to Japan because they can work on a student visa. When they arrive, they obtain two or three jobs, work 40-60 hours, sleep five or less hours per night, and send money back to their families. Some are genuinely interested in learning Japanese, but many see school as an irritating, expensive obstacle to overcome while they’d rather be working, socializing or sleeping.

I had no idea I would be in a small privileged minority in going to language school “for fun,” and I had to invest a large amount of thought and engagement to come to terms with the reality. When I studied abroad in college, all the other students were there because they wanted to be, so I assumed Japan would be the same.

My first roommate and I formed a strong respect and bond with each other, especially regarding our different backgrounds (she is from Vietnam). In fact, I probably learned more from Nhu Y than any other person in Japan. One of the most important lessons she taught me, just by being herself, was to appreciate my privilege with regard to language and culture learning.

Lesson 9: Tell Me Whom You Love And I’ll Tell You Who You Are

I loved my professional role as a nurse practitioner, and the status it afforded me in society. I actively downplayed the prestige, and assiduously avoided exploiting it, but it was always present. One reason I decided to move abroad was because I could sense my ego getting too big for me to handle, and needing to be taken down a notch. I certainly got what I wished for in that, in spades.

But I also truly-madly-deeply identified with my role as a health care professional working in an underserved area with people who otherwise would not receive any medical attention. It was so easy for me to explain who I was by talking about my job and the difference I was making in the world.

But as a Japanese student in Japan, I lost that identity and had to create a new one, essentially from scratch. The default identities for those in my position were poor fits as well. #1: “studying Japanese to try to get into college in Japan” simply wasn’t true, and #2: “studying to be a Japanese teacher back in the USA” didn’t describe me either.

So I had to recreate my identity essentially from scratch, without relying on my profession as a crutch. The online work I was doing was too hard to explain for most people to understand, so that didn’t help either.

So I started fresh, and did my best, and learned every day about what I value, love and care about, and used these as a base on which to form my newly-minted identity.

May - Lost & Found

Lesson 10: If You Don’t Get Lost, You May Never Be Found

The easiest example to explain is that I rented a bicycle for my six months in Okinawa, and would frequently take off on my bike in a random direction, just to see what I would find. I couldn’t read the street signs, the store signs, or even most of the map I carried, but I had fun seeing where I ended up.

I “got lost on purpose” emotionally, mentally and professionally as well. The emotional and mental forests I wandered through helped me reintegrate my self-image and identity, and during a professional wandering I realized that I intensely missed seeing patients and taking part in patient care. These nuggets I filed away for future reference as I continued to wander and find myself.

Lesson 11: A Stranger Is Just A Friend You Haven’t Met Yet

Relationships have always been important to me, but my time in Japan helped me realized the extent to which they rule my subconscious and conscious value systems.

I was effectively cut off from my usual social support network, so I was forced to develop a new one despite the language barrier. Because of Japanese cultural norms and mores, strangers are unfailingly polite. However, again because of those same norms and mores, in addition to my status as an outsider/foreigner, the Japanese are extremely difficult to engage in “true-friend” type relationships.

I learned to appreciate and take advantage of the unfailing politeness. I could ask for directions a dozen times without batting an eyelash, and always receive help to the level of each person’s ability. If I didn’t understand the first person, I would go a block or two in a random direction and simply ask someone else, referencing the few words the first person said that I did understood, and slowly make my way to my destination. In turn, I unfailingly helped others as well, something I do by nature.

I formed deep bonds with several individuals who started out as complete strangers, and developed a beautifully interwoven network of support with these new friends. We helped each other muddle through our struggles, and celebrated our successes together. In short, we lived life together.

June - Screw It Up

Lesson 12: “[Cultural Appropriation]… Need Not Be Synonymous With Exploitation” – Bell Hooks

- Bell Hooks

A Hindu friend put a Bindi on my forehead while we were horsing around in his restaurant. Acutely conscious of the horrors of cultural appropriation perpetrated by people of my skin color against others, I immediately went to take it off. He said I looked beautiful while wearing it, and that it made him happy. He asked me to leave it on, at least for a little while. I froze, undecided and indecisive.

I decided to leave the bindi on my forehead until it fell off naturally, and use the time to reflect on cultural appropriation, relationship and religion. This experience turned into five days of the most intense cultural learning of my life. I rapidly noticed that most people, including my Hindi classmates, didn’t care at all that I was wearing the bindi. The few comments I received, when I received any at all, were overwhelmingly positive.

Before this experience, I thought “cultural appropriation” was a horrible act to be avoided at all costs. After this experience, I understand it to be relative, like everything else in life, to your relationship to the culture/people involved, your position/status, your purpose, your goal and your attitude.

I was almost disappointed, but definitely relieved, when the bindi fell off while I was washing my face five days later. I was able to shelve my intense reflections and process the experience at a more normal rate after that. I went on to wear a bindi several times when my friend would again decorate me with one, and breathed much more easily having been through my personal reflection on what it meant to me.

Lesson 13: If At First You Don’t Succeed, Try, Try Again

I established a personal goal to make at least 1,000 mistakes a day in Japanese. Sometimes I would make the same mistake over and over again, but other times I would make entirely new mistakes, or someone would correct me. I didn’t much care which, as long as I was making lots of mistakes. I know 1,000 sounds like a lot of screw-ups, but that equates to about two hours of speaking in Japanese, since I make various errors per sentence attempted/spoken.

I took this attitude because I have a perfectionistic tendency, and perfection is the death of language learning, or at least enjoyable language learning. You can stare at a verb conjugation table for hours on end, and memorize it perfectly, and that’s great. But you won’t be able to use that knowledge until you try it out on someone and start screwing it up by playing with it to communicate your ideas and stories with another human being.

So I screwed up as much as possible, and disported myself thusly and enjoyably.

July - Bad Things Happen

Lesson 14: A Fool And Their Money Are Soon Parted

Then I landed in Bangkok.

My first impression of Bangkok: If Los Angeles is Red Hot Chili Pepper’s “Under The Bridge,” then Bangkok is Los Angeles screaming down the road high on meth steering a motorbike one-handed while waving to a friend in the rain with a broken headlight.

I was swindled six ways to Sunday within minutes of setting foot in Bangkok, the first stop of my Southeast Asia summer vacation. I was bewildered, nowhere near prepared for the teeming mass of shady humanity that bursts at the seams in that frenetically paced place.

Fortunately, Thailand is so inexpensive that even though I was ripped off with wild abandon that first day, the damage to my pocketbook was manageable, if not so much to my pride.

I rapidly learned to distrust, and take care, and triple-check everything in advance and after the fact.

And to dislike Bangkok.

Lesson 15: Accidents Will Happen

However, after a few minutes in class, my head started to hurt much worse and I started having trouble thinking, and feeling nauseous. I knew these things were Bad Signs, and asked for help.

My multilingual school office friend rushed me to the nearest hospital, then to a bigger hospital, then to a specialty (neurology) hospital. I was worsening steadily, and could barely respond coherently or walk unassisted by the time I was admitted to the neurology ward. I just wanted to go to sleep, but I knew that to be a Bad Idea.

The neurologist checked me out within five minutes, and they wheeled me the 100 feet (30 meters) to the MRI suite less than an hour later. Another hour after that, I was feeling somewhat better, and my thinking had cleared up. The doc showed me the considerable bruising I had sustained to my scalp, but that my brain was completely clear.

I breathed a heavy sigh of relief, both for being well, and so well taken care of. The entire episode cost me four hours, fifty-five dollars and three days of bed rest.

August - Just Do It

Lesson 16: Don’t Give In To Your Fears

I acted brave my entire time in Japan. But the truth is I was just as afraid as the people around me. I just refused to acknowledge it or let it slow me down from trying new things.

For example, I was terrified about climbing Mount Fuji (富士山), but I did it anyway. My stomach roiled the whole time on the trip to get there. But I climbed it anyway, resulting in one of the most memorable and shareable moments from 2014. I stood at the top of the mountain with my dad, watching the sunrise together and thinking “Holy crap… we did it!” And then getting all mushy thinking what a great bonding moment it was. After that I started shivering violently from the frigid wind slicing through my not-quite-enough layers of heavy clothing, and the moment was over.

But that’s a moment I’ll always treasure.

So I gritted my teeth and designed and implemented a “super duper tourist” day in Kyoto, hitting four or five widely separated tourist attractions, preemptively hating myself for it the whole time I was planning it.

However, that day in Kyoto was one of my favorites in my whole time in Japan. I loved it, and I loved the temples, the forests and the gardens, even though we saw them at light speed.

From this, I learned to spend less time judging myself and others, and more time listening to and following my heart.

Lesson 17: You Will Never Ever Be Good Enough. And That Has To Be Good Enough.

Even in “small town USA,” most folks have come across individuals who look “different from us” but grew up nearby and speak with the local accent, either because their families have lived there for generations, or because they are 2nd or 3rd generation immigrants who were born here or immigrated very young.

This is most emphatically NOT the case in Japan. In fact, the opposite is true.

Luke, our main guide up Mount Fuji, was a White man in his late twenties. His parents were born in the United States, but immigrated to Japan decades ago. They spoke English with Luke at home in Tokyo, but most of their daily life was Japanese. As a second-generation immigrant growing up in Japan, Luke’s personal culture is largely Japanese, with little touches of American around the fringes. He has only been to the United States a few times to visit, and his situation is similar in many ways to the folks in the first two paragraphs above.

In the United States, we call these individuals “Mexican-American,” “Asian-American” or another word indicating multiple identity/root systems, or sometimes simply “American.” In Japan, however, Luke and others like him are looked on with fear, disgust, confusion and distrust. He is seen as an “American” who “doesn’t know his place.” Because his Japanese is “too perfect” and this made other Japanese people too uncomfortable, Luke was turned down for many jobs and outcast from group and social activities. Luke had to start his own business as a tour guide to find work, and works mainly with American tourists.

Our other guide was Brent, a friend of Luke’s since grade school, and another second-generation immigrant in a similar situation. However, Brent’s parents had an older son struggling against the same prejudice as Luke, recognized this situation, and decided to send Brent to live with relatives for four years in Denver when he was a teenager. They wanted his Japanese to be “less than perfect,” since native-level fluency had caused Luke and Brent’s older brother so much strife.

And you know what? It worked. Someone like me, with barely-understandable Japanese, who breaks many cultural norms but tries hard to be respectful, is accepted with fairly open arms. Someone like Brent, with near-flawless Japanese and nearly perfect ability to navigate Japanese cultural norms, but whose accent is still audible in complex situations, is accepted with open arms.

But get “too big for your britches” by being fully native, and you will be distrusted, disliked, outcast, discriminated against and mistreated. Sounds familiar, perhaps similar to how we treat people of color/minorities in the US, especially those with poor English attainment, doesn’t it? And kind of creepy, right? It gives me shivers just thinking about it.

I spent hours discussing this with Brent and Luke on our hike. Even so, as I write about the situation four months later I am struggling to wrap my brain around it.

Life lesson? The world is really screwed up, but be yourself, even if no one wants you to be. You may never ever be good enough for them, but who you are is good enough for you, me, and the other humans that matter.

Lesson 18: When The Going Gets Tough, The Tough Run Away

So I did what any brave and thoroughly overwhelmed person would do: I ran away. I hopped on a couple buses and three hours later landed at my American friend Adrian’s house for the week. Adrian offered to host me for those five days, and to use the home Wifi whenever I wanted to, including for my 3am Skype interview.

While Adrian was at work teaching English to Japanese high schoolers every day, I pounded furiously away at my keyboard, getting oodles and oodles of work done. I cooked Adrian dinner almost every night, and after dinner, we would talk about life, the universe and everything.

My first three months in Japan, I steadfastly refused to speak a single word of English. The few times I did open up, it was almost always in Spanish. My spoken Japanese rocketed upward in fluency those three months, but I felt isolated and struggled with social support.

When I got to Adrian’s house, though, the dam broke and I opened up in English about my trials and tribulations. Adrian had been living in Japan for three years, and was a great listener. I had no idea I had so much pent up emotion and thoughts that weren’t coming up because I was so pigheadedly stubborn about my “language learning process.”

My time hiding away from the world at Adrian’s house taught me to balance my desire to learn language with my need for relationship and social support in my native language and culture. I still spoke mostly in Japanese for the rest of my trip, but made much more allowance for my social-relationship needs from that point on. Self-care life lesson learned.

Lesson 19: Everyone Smiles In The Same Language

About one third of the women in Malaysia that I encountered wore traditional garb, covering their arms, legs and heads. Of those, one third wore all black, covering everything except for their eyes. Despite my oh-so-sophisticated, well-traveled exterior, I was a little afraid of the women in all black, and the men with them. They seemed so… foreign. Weird. Strange. Scary. Unknown.

She became another human being to me, rather than something to be misunderstood and feared. And I was changed.

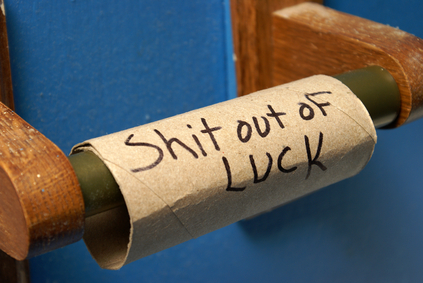

Lesson 20: Call A Jack A Jack, Call A Spade A Spade.

In addition to the soaring moments of new knowledge and learning and bonding, I experienced some pretty shitty situations as well. In some cases, the shit was literal, like when I had to pee in a hole in the ground, or stayed in a hostel with unidentified sticky smelly things on the walls, bed and floors.

Sometimes the shit was figurative, like when my data backup plan crashed and I spent my precious few hours in Madrid ignoring the beautiful plazas and incredible gastronomy to try to find a department store to sell me a hard drive.

I complained about those things when they happened, and processed them as much as I needed to. I talked about them, blogged about them, and learned from them. But as for the end of year review, I mostly experience them as “shit happens” and move on. It’s amazing what perspective and a little time will do for these things, isn’t it?

September - Work It Out

Lesson 21: Necessity Is The Mother Of Invention

Each one of those places had different ways of connecting to the Internet, different levels of uptime, different hours of operation, radically different time zones, many kinds of distractions, including loud noises such as construction work and screaming children, frequent disruptions and cross-continent travel.

But it all happened quite smoothly. I set this job as a #1 top priority numerous times, because it is something that truly matters to me. With the amount of hoops I jumped through to secure this position and how much I enjoy it, I have no intention of relinquishing it any time soon, no matter where I am. Also, having gone through the above, I feel much more confident that I can make it happen, through whatever adversity.

Lesson 22: Laughter Is The Best Medicine

April’s husband, myself and another friend went out to play one fine day, and created joy together. April had been begging me to go to the “American Village” for months, but I had previously refused, because I didn’t want to speak English or be surrounded by Americans.

At this point, though, I was willing to do just about anything to see her smile again, so we piled into the rental car and off we went to experience Americana in Okinawa. Ironically, despite all the Stars & Stripes, Britney Spears, military surplus and cowboy gear, we did not see a single other foreigner during our four hours in the American Village.

We didn’t do anything special, and we started with almost no plans. We shared a delicious meal, walked around, played in the water, made bad jokes about me being the only American in the American village, had some pizza and reluctantly made our way back home. It was delightful, magical, and cost only a small amount of money.

And it was one of the best days of my life.

Lesson 23: Honesty Is The Best Policy, But The Truth Hurts

Some of these mistakes were truly mistakes, and I should have known better, and apologized as soon as I realized/knew. It hurt to hear that I’d been that rude and didn’t even know it. Many of the “mistakes,” though, were not mistakes but rather differences in culture. Some of them were even mutually exclusive cultural differences in value systems.

For example, we had a discussion one day about the Japanese and Vietnamese reverence for shyness and collectivism versus the American reverence for boldness and individualism. Both are true and right and just, but they jostle each other restlessly when they are shoved into a small area for too long and can’t get away from each other. This results in misunderstandings and hurt feelings, and coming to terms with the issues can be difficult, because the parties have such radically different values.

Many friends and family asked me after I shared that with them “why did they all have to be -your- mistakes? If a lot of these were ‘cultural differences’ rather than mistakes, why didn’t she take responsibility for some of them?”

#1 – My roommate was Asian (Vietnamese), and her norms and mores were much closer to Japan, where we were living, than mine. Learning and listening from her also improved my experience in Japan. Win-win-win.

#2 – I had just made several major faux pas and badly hurt her feelings, and needed to make up for it. I needed to keep my mouth shut, so I did.

#3 – In my last three months in Japan, I lived with three Vietnamese girls. I was outnumbered, and it was sink or swim time. Not offending her also meant much more peace in the home, because I wouldn’t offend the other two either.

#4 – That’s how I roll, and it doesn’t bother me in the least that the interaction wasn’t “fair.” I am grateful and happy that I got to learn from her. Yeah, it was hard to hear what a jerk I’d been by Vietnamese standards, but at least now I had a roadmap for getting better.

October - Normal Is Relative

Lesson 24: In For A Penny, In For A Pound

I had no interest in being part of the running of the bulls, but I was incensed by being told I was not allowed because I am a woman. I was pissed off enough that I decided to “accidentally” join in. I figured I could stay far away from the bull, just like the men do, and walk back and forth with the crowd, trumpeting how cool I was to be a girl on the bull-running street and proving them all wrong.

However, I quickly learned that if you’re going to bust open the gender divide, you have to take the good with the bad.

As I proudly walked from the side street into the main thoroughfare where the running of the bulls was taking place, posture erect and head held high, I was struck by the sense of quiet expectation, and the lack of people in this part of the street.

Apprehensive, I glanced over my right shoulder, and saw the bull charging straight at me from less than twenty feet away!!! I ran like hell and leaped gracefully over a low wall and stumbled unceremoniously to the ground on the other side, rolling to a stop among some soft greenery. It turned out to be a mint garden, so in spite of my aroma of sweat and fear, I smelled minty fresh afterward.

And a little more humble.

Lesson 25: "Normal Is Just A Setting On Your Dryer" – Patsy Clairmont

My first major culture shock was getting to Norway. I was stunned into utter silence and stillness as I gawped in awe at all the tall White people. Now granted, I grew up in small town central Wisconsin, well-known for its surplus of tall White people, many of whom are of Norwegian ancestry, myself included. However, after so many months in Okinawa, seeing the other people in the Oslo airport blew my mind to smithereens.

I experienced deeper and more intimate culture shock on arriving in the Azores to a standard Portuguese diet of fish, creamy sauces, bread, lots of meat, and gads of potatoes. No sushi, no weird Asian vegetables, no chopsticks, and tons of sweets. My brain and gut experienced several meltdowns related to differences in the food. I ate oatmeal every single day to give my digestion and brain a break.

Oh, and a completely different language than the one I’d dedicated the past 6-12 months learning. But that was the easy part compared to the culture shock.

I sometimes hear and use the word “reverse” culture shock, but I don’t feel like it applies to me anymore. I’m moving around too much, and integrating too much of what I am learning into my core vision of self, to feel like it’s a “reversal” process. The “shock” part certainly applies, though, as my “normal” bounces around like a steel marble clanging around in an otherwise-empty dryer.

November - Sing & Learn

Lesson 26: A Bird Does Not Sing Because It Has An Answer. It Sings Because It Has A Song.

However, I sang way less in Japan than I normally do, and for that reason if for no other, I doubt I will ever live there again. Being noisy is the epitome of rudeness in Japanese culture, and would get me disgustedly labeled “Stupid American” faster than I could finish one line of whatever song I was singing. My apartment complex was eerily silent, despite paper-thin walls, because no one made any noise. Those who do were immediately shushed and socially castigated. Not my favorite part about Japan, for sure.

Quietness is a virtue, and most Japanese hobbies involve minimal noise. Tennis. Zen archery. Origami. Judo. Karate. Sumo. Ikebana flower arranging. Silent masked theater. Manga. Tea ceremonies. Calligraphy. The only major exceptions are pachinko and karaoke bars, which are carefully soundproofed and rarely intrude into the quietness outside their walls.

I’m discounting the Japanese insanity for baseball as an outlier.

The moment I stepped foot back into Tucson, though, I zoomed straight over to church, where I belted out hymns and hugged my old choirmates during the “peace be with you.” The choir members joyfully sang behind me and winked at me when they could catch my eye, as did I at them.

I begged the choir director incessantly but oh-so-politely until he let me join for the two months I would be back in Tucson, despite normally only accepting new choir members every August. Choir, and singing in general, has easily been one of the highlights of being back in Tucson these past few months.

Lesson 27: Learning Is A Treasure That Will Follow Its Owner Everywhere

The speed with which my relatives’ necks whipped around to face me after making that comment, and the incredulous looks on their faces indicated to me the depth of doo doo I had just stepped in. I was able to largely pass it off as a language mistake, but I shaped up fast after that reaction, and set my prejudices aside.

I opened my ears, my eyes and my heart to what was happening around me, and recognized how integral this event was to family and island culture, and didn’t stick my foot in my mouth again. I kept my mouth zippered firmly shut, observed, and learned about the baptism, the rituals around it and what it meant to them.

菜食主義者

However, I don’t plan to do so, for several reasons. #1, it is exceedingly rare that I actually need it, and #2, it feels SO GOOD when I can write it down and show it to them. I feel on top of the world when it happens, and vindicated in choosing to study the Kanji, which otherwise have such little practical use in Western lifestyle.

For whatever reason, learning the Kanji makes me inordinately happy. I continue to study my online flash-card system thirty minutes every day, before I even get out of bed, because it’s something I am highly motivated to learn, and enjoy.

December - Hindsight Is 20/20

Lesson 28: Absence Makes The Heart Grow Fonder

I tried not to complain about Portugal, but the culture shock I was experiencing made it hard to appreciate the many wonderful things and people I had access to there that I didn’t in Japan. I did my best to express as much gratitude as humanly possible, and I did have a lovely experience there, but I know I came across as unhappy. And I was, to some extent.

Similarly, when I got to the USA, I immediately started glorifying all things Japan and Portugal, to the detriment of the USA, and again sweeping the negatives under the rug.

It wasn’t nearly as pronounced as when I arrived in Portugal, though, for several reasons. Firstly, I was prepared for the culture shock this time, and had had a month in Portugal to deal with the Asia-to-Europe culture shock. Secondly, I have a wide network of social support in Tucson of friends in different arenas of my life and interests that actively and potently cushioned my landing.

Those daily annoyances sure do disappear fast when I want to brag about how cool my adventures were. Now that is a lesson I shall endeavor to remember.

Lesson 29: “We Don’t See Things As They Are, We See Them As We Are” – Anais Nin

When I caught sight of her through the café door, however, I froze physically and mentally, and couldn’t utter a single word. She came up and hugged me, excited to see me, and started talking to me. I gawked at her in wide-eyed wonder, and all my locked-up mind could come up with was to stutter out “you’re… you’re… so… TALL!?!” In my brain, something felt incredibly wrong, but I had no clue what it was.

My friend laughed uncomfortably, a little unnerved, and led me to her table inside the café. I felt shaken by the power of my own response, not understanding where it came from. My brain/memory, having been around so many Asian women in Okinawa, had resized my friend downward by at least six inches. And I don’t think it was just her physical size that my brain decided to modify to fit my new definition of “Asian according to the gospel of Sam in Okinawa.”

My friend’s parents are Asian, but she was born in the US, and her personal culture is largely American, with little touches of Asian around the fringes. When I sat down at the table and looked at her again, something clicked, and she suddenly represented my whole worldview since coming back from Okinawa, sliding “just so” and locking into sharp focus.

At that moment, my brain returned to the USA, and I knew myself:

My name is Samantha Alvarez. I am an American, but I have little touches of Latin, Asian and Western European around the fringes.

It’s nice to meet you.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed